Whether you’re a passionate tea drinker, a curious beginner, or a hospitality professional seeking to deepen your knowledge, understanding the language of Japanese tea is essential to appreciating its culture, rituals, and craftsmanship. In this glossary, we’ve gathered45 key terms—from the foundational to the poetic—to help you navigate the rich and nuanced world of Japanese tea culture.

From the tools of the tea ceremony to the names of rare teas and production techniques, each entry invites you to discover tea not just as a beverage, but as a way of life.

Amami (甘み) - SweetnessIn the context of tea, it refers to the natural sweetness derived from amino acids, particularly L-theanine, found in high-quality Japanese green teas. This sweetness is especially prominent in shaded teas like Gyokuro and Kabusecha, and contributes to the balanced, umami-rich taste profile that defines premium Japanese tea.

Asamushicha (浅蒸し茶)Asamushicha refers to lightly steamed green tea, where the steaming time is brief—typically 10 to 30 seconds. The result is a tea with clear, golden liquor, a refined aroma, and a flavor that leans toward brighter astringency. The leaves maintain more of their structure, making it a favorite among tea purists seeking a more delicate and traditional Sencha experience.

Atama (頭)In Japanese tea grading, Atama refers to the larger, more mature tea leaves found in the upper part of the plant. These leaves contain a higher concentration of caffeine, astringency, and umami, resulting in a stronger, more robust flavor. While less tender than younger leaves, Atama is often used in blends to enhance body and depth.

Cha (茶)Cha simply means “tea” in Japanese and is the root of many tea-related terms such as Sencha (steamed tea), Matcha (powdered tea), and Ryokucha (green tea). While often referring to green tea in Japan, the term can denote any type of tea depending on context.

Chadō / Sadō (茶道)Translated as “The Way of Tea,” Chadō (or Sadō) is the spiritual and aesthetic practice of the Japanese tea ceremony. Rooted in Zen philosophy, it represents a harmonious blend of etiquette, mindfulness, and hospitality (omotenashi). The practice goes beyond brewing tea—it is an art form centered around respect, purity, tranquility, and connection.

Chanoyu (茶の湯)Literally meaning “hot water for tea,” Chanoyu is a synonym for Chadō and refers to the ritual of preparing and serving Matcha in a formal setting. It involves precise movements, seasonal aesthetics, and traditional tools, all contributing to an atmosphere of mindfulness and quiet appreciation.

Chagama (茶釜)A Chagama is the iron kettle used to boil water during a tea ceremony. It often sits atop a hearth or brazier in a tea room and is a symbol of purity and calm. Its soft bubbling sound adds to the sensory harmony of a tea gathering.

Chasen (茶筅)The Chasen is a handcrafted bamboo whisk used to prepare Matcha. With delicate, finely carved tines (typically 80–120), it’s used to vigorously whisk Matcha into a smooth, frothy suspension, essential to traditional Japanese tea ceremony.

Chasen-naoshi (茶筅直し)Also known as Chasen-tate (茶筅立て), this is a ceramic or porcelain stand used to hold and maintain the shape of your Chasen after use. It helps extend the life of the whisk by preventing deformation and promoting proper drying.Preserve your whisk’s shape—discover our elegant Chasen-naoshi holders.

Chashaku (茶杓)A Chashaku is a bamboo scoop used to measure Matcha powder during tea preparation. Its graceful shape and minimalist design are part of the refined aesthetic of the tea ceremony. Each scoop typically holds about 1 gram of Matcha.Experience tradition in every scoop—browse our handcrafted Chashaku selection.

Chashi (茶師)A Chashi is a Japanese Tea Master, someone with deep expertise in evaluating, blending, and refining tea leaves. Though it’s not a certified title, it’s a role earned through years of hands-on experience and peer recognition. A Chashi is responsible for preserving tea quality and crafting signature flavor profiles, much like a master sommelier in the world of wine.

Chabashira (茶柱)Chabashira refers to a tea stem standing upright in your cup—a rare and auspicious sign in Japanese culture. It is said to bring good luck and positive fortune, making it a charming detail that connects everyday tea drinking with tradition and superstition.

Chawan (茶碗)A Chawan is a tea bowl used primarily in the preparation and drinking of Matcha. Each chawan is unique, often handmade, and reflects the season, the style of the ceremony, and the host’s intention. The same word is also used to describe a rice bowl in everyday Japanese life, highlighting the close cultural ties between food, tea, and ceramics.

Chumushicha (中蒸し茶)Chumushicha refers to medium-steamed green tea, where the leaves are steamed for around 30 to 60 seconds. This process results in a balanced cup—less astringent than lightly steamed tea (Asamushicha), yet not as dense or opaque as deep-steamed Fukamushicha. It offers a pleasant harmony of sweetness and clarity, ideal for daily drinking.

Fukamushicha (深蒸し茶) Fukamushicha is deep-steamed green tea, where the leaves are steamed for 1 to 3 minutes. This extended steaming process results in a vibrant green color, less astringency, and a mellower texture. The tea leaves become softer, creating a smooth, umami-rich taste that is full-bodied yet approachable.

Genmaicha (玄米茶) Genmaicha is a blend of green tea and roasted brown rice, known for its nutty aroma and comforting, toasty flavor. The roasted rice adds warmth and depth, making it a favorite for casual, everyday drinking. Often enjoyed with meals, Genmaicha is both gentle on the stomach and low in caffeine, making it suitable for all ages and times of day.

Gyokuro (玉露) Gyokuro, meaning “jade dew,” is one of the finest Japanese green teas, prized for its sweetness, intense umami, and low astringency. It is grown under shade for about three weeks prior to harvest, which boosts L-theanine and reduces catechins, resulting in a silky, deep flavor. Brewed at lower temperatures, Gyokuro delivers a luxurious, velvety infusion with a lingering finish.

Hōjicha (ほうじ茶) Hōjicha is a roasted Japanese green tea, made by pan-roasting leaves at high temperatures. This roasting process removes bitterness and caffeine, leaving behind a tea with a toasty, nutty aroma and a smooth, earthy flavor. Naturally low in caffeine, Hōjicha is often enjoyed after meals or in the evening, and is even suitable for children. Its comforting aroma makes it a beloved choice in Japanese households.

Ichigo Ichie (一期一会) Ichigo Ichie translates to “One Time, One Meeting,” a cherished concept in Japanese tea culture. It expresses the idea that every encounter is unique and unrepeatable, urging both host and guest to treat each moment with sincerity and appreciation. In tea ceremonies, this philosophy reminds us to be present, mindful, and grateful, as no two gatherings are ever the same. It embodies the spiritual essence of Chadō.

Ippuku (一服) Ippuku means “a bowl of tea” or more broadly, “a tea break.” It refers to the act of drinking tea prepared by the host—a small but meaningful pause that creates space for reflection, connection, or quiet appreciation. In everyday Japanese, the term is often used to describe taking a short rest with a warm beverage.

Kabusecha (冠茶) Kabusecha is a shade-grown green tea, covered for 7 to 14 days before harvest. This method reduces sunlight, enhancing the tea’s umami and sweetness while softening bitterness. It sits between Sencha and Gyokuro in both process and flavor—offering more depth than standard Sencha with a lighter body than Gyokuro.

Kaiseki (懐石) Kaiseki is the traditional multi-course meal served before a formal tea ceremony. Originally, it emphasized seasonal ingredients and simplicity, with a focus on preparing the body for Matcha. Today, kaiseki ryōri has evolved into a celebrated form of fine dining in Japan, yet its roots in tea culture and mindful hospitality remain. The term cha-kaiseki (茶懐石) is used to differentiate tea-based Kaiseki from modern haute cuisine.

Kancha (寒茶) Kancha, meaning “cold tea,” is a rare type of green tea harvested in winter (December to February). The colder temperatures slow leaf growth, producing a tea that, when boiled, reveals mellow sweetness and soft astringency. This seasonal specialty is prized for its clean finish and warming qualities, offering a deeper connection to nature’s rhythm.

Kintsugi (金継ぎ) Kintsugi, meaning “golden joinery,” is the traditional Japanese art of repairing broken ceramics using lacquer mixed with gold powder. Rather than hiding flaws, it celebrates them, transforming cracks into part of the object’s history and beauty. In tea culture, Kintsugi is more than restoration—it’s a metaphor for resilience, imperfection, and the appreciation of time’s passage. Many chawan (tea bowls) used in ceremonies bear these golden veins as a sign of reverence.

Koicha (濃茶) Koicha means “thick tea” and is a ceremonial preparation of Matcha using approximately 4 grams of powdered tea and minimal water. The result is a rich, syrupy texture with bold umami and profound depth. Served in the most formal tea gatherings, Koicha is typically shared among guests from a single bowl—an act symbolizing unity and respect in the tea room.

Konacha (粉茶)Konacha translates to “powder tea,” but unlike Matcha, it refers to fine particles and tea dust left over from the production of Sencha or Gyokuro. Commonly used in sushi restaurants for its brisk, bold flavor and quick infusion, Konacha is a practical and economical tea with strong character.

Kukicha (茎茶) Kukicha, or “stem tea,” is made primarily from the stalks and stems of young tea leaves, particularly from Shincha (first flush) harvests. It has a unique profile: light, slightly creamy, and naturally sweet, with a refreshing aroma. Lower in caffeine than leaf-only teas, Kukicha is soothing, everyday-friendly, and a hidden gem in the Japanese tea world.

Kyūsu (急須) A Kyūsu is a traditional Japanese teapot, most commonly made of clay and designed for brewing green tea. The classic style features a side handle and an internal mesh or clay strainer, allowing smooth pouring while retaining the leaves. Regional craftsmanship—such as Tokoname-yaki or Banko-yaki—adds value and artistry to each Kyūsu.

Ma (間)

Ma is a profound concept in Japanese aesthetics, often translated as “space” or “interval.” In tea culture, it refers to the timing, rhythm, and silence that exist between actions or conversations during a tea gathering. Ma is what creates presence and mindfulness—whether it’s the pause before serving tea, the space between sips, or the physical simplicity of the tea room. It fosters a deeper connection between host and guest, honoring the beauty found in stillness.

Matcha (抹茶)

Matcha is a finely ground powder made from shade-grown green tea leaves, traditionally used in Japanese tea ceremonies. Known for its vivid green color, smooth texture, and rich umami, Matcha is whisked with hot water using a Chasen (bamboo whisk) to produce a creamy, frothy drink. It’s also high in L-theanine, antioxidants, and caffeine, offering a calm yet focused energy. Today, Matcha is also popular in modern cuisine, from desserts to lattes.

Mizusashi (水差し) A Mizusashi is a lidded container used to hold fresh water during a tea ceremony. It’s an essential tool in Chadō, used for rinsing utensils, replenishing the kettle, or adjusting water temperature. Often crafted from ceramic, lacquerware, or glass, its design reflects the season and aesthetic of the tea gathering.

Mecha (芽茶) Mecha means “bud tea” and is composed of the youngest tips and small leaf buds collected during the processing of high-grade teas like Gyokuro or Sencha. It has a concentrated flavor profile, with higher levels of umami and caffeine, offering a bold, full-bodied cup ideal for experienced tea drinkers.

Natsume (棗) A Natsume is a lidded container used to store Matcha during a tea ceremony. Named for its resemblance to the jujube fruit (natsume in Japanese), it’s typically made from lacquered wood or ceramic and is used in informal usucha (thin tea) gatherings. The Natsume’s smooth curves and seasonal designs contribute to the visual harmony of the tea setting.

Omotenashi (おもてなし) Omotenashi represents the Japanese spirit of hospitality, characterized by sincere, selfless service and anticipating the guest’s needs without expectation of reward. In the context of tea, it means serving each bowl with intention, care, and respect. Omotenashi is not simply politeness—it is empathy made tangible, and a central pillar of Chadō.

Ryokucha (緑茶)Ryokucha is the general term for green tea in Japan, referring to unfermented teas made from Camellia sinensis. This category includes Sencha, Matcha, Gyokuro, Kabusecha, Hōjicha, and others. Japan’s green teas are typically steamed rather than pan-fired, giving them a vibrant green color, vegetal aroma, and umami-rich flavor.Discover our full range of Ryokucha and explore Japan’s green tea spectrum.

Sencha (煎茶) Sencha is the most commonly consumed green tea in Japan, made by steaming, rolling, and drying fresh tea leaves. It offers a bright, grassy aroma with a balance of umami, sweetness, and a gentle astringency. Sencha varies by region, season, and steaming time—ranging from light and floral to deep and savory.

Shibumi (渋み) Shibumi describes the subtle, refined astringency found in high-quality Japanese green tea. It’s not an overpowering bitterness, but rather a delicate sharpness that adds depth and structure to the flavor. In a broader cultural sense, Shibumi is also an aesthetic ideal—quiet elegance, understated beauty, and complexity beneath simplicity.

Shincha (新茶)Shincha, or “new tea,” refers to the first flush of tea harvested in early spring—typically April to May. These young leaves are rich in aroma, sweetness, and nutrients, with a vibrant, fresh character that celebrates the new season. Shincha is considered a limited-time delicacy and is highly anticipated by tea connoisseurs each year.

Teishu (亭主)The Teishu is the host or tea master in a tea ceremony, responsible for preparing and serving the tea in accordance with the traditions of Chadō. More than just serving tea, the Teishu embodies hospitality, precision, and presence, guiding the rhythm and ambiance of the gathering while upholding the values of harmony, respect, purity, and tranquility.

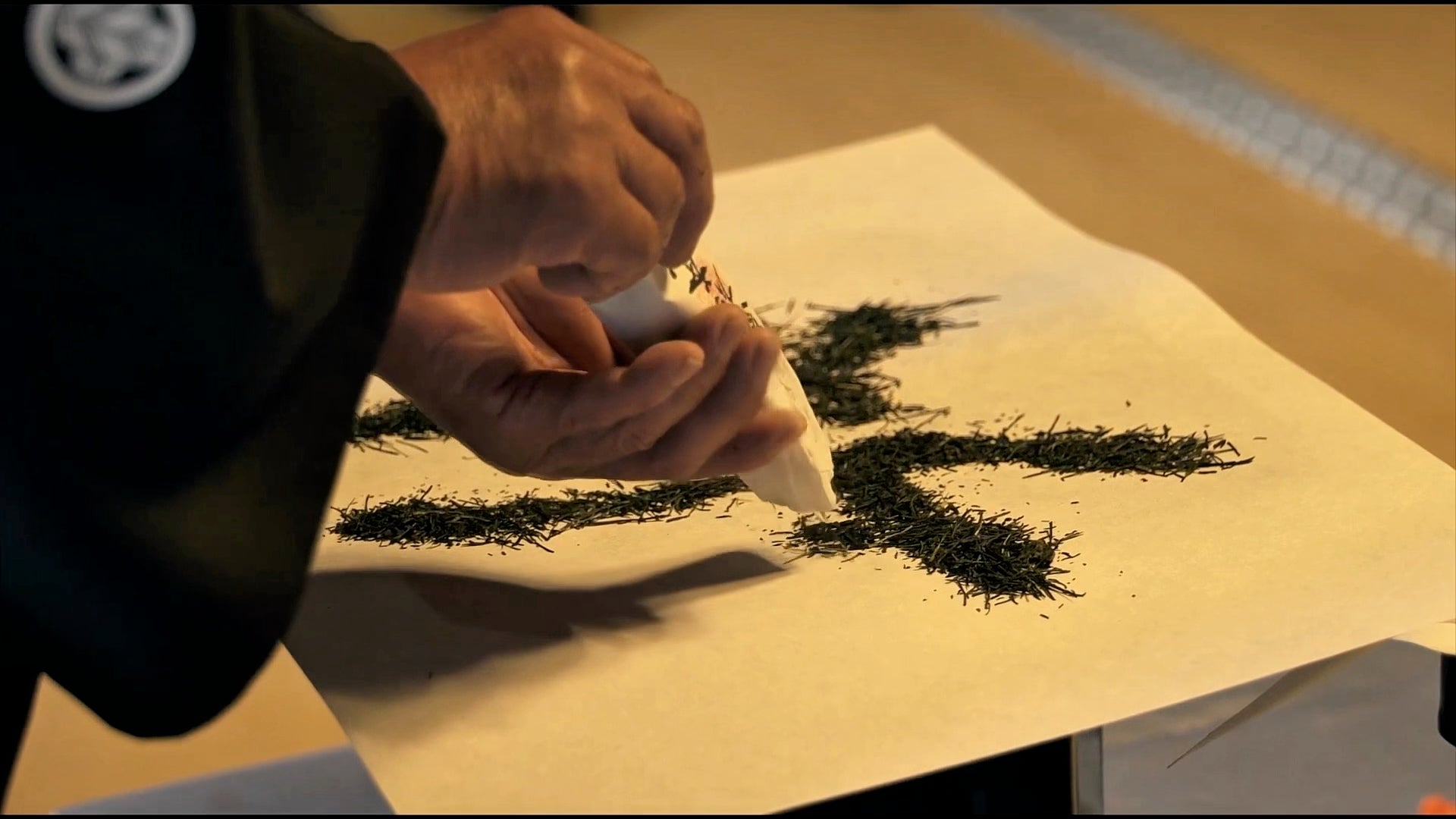

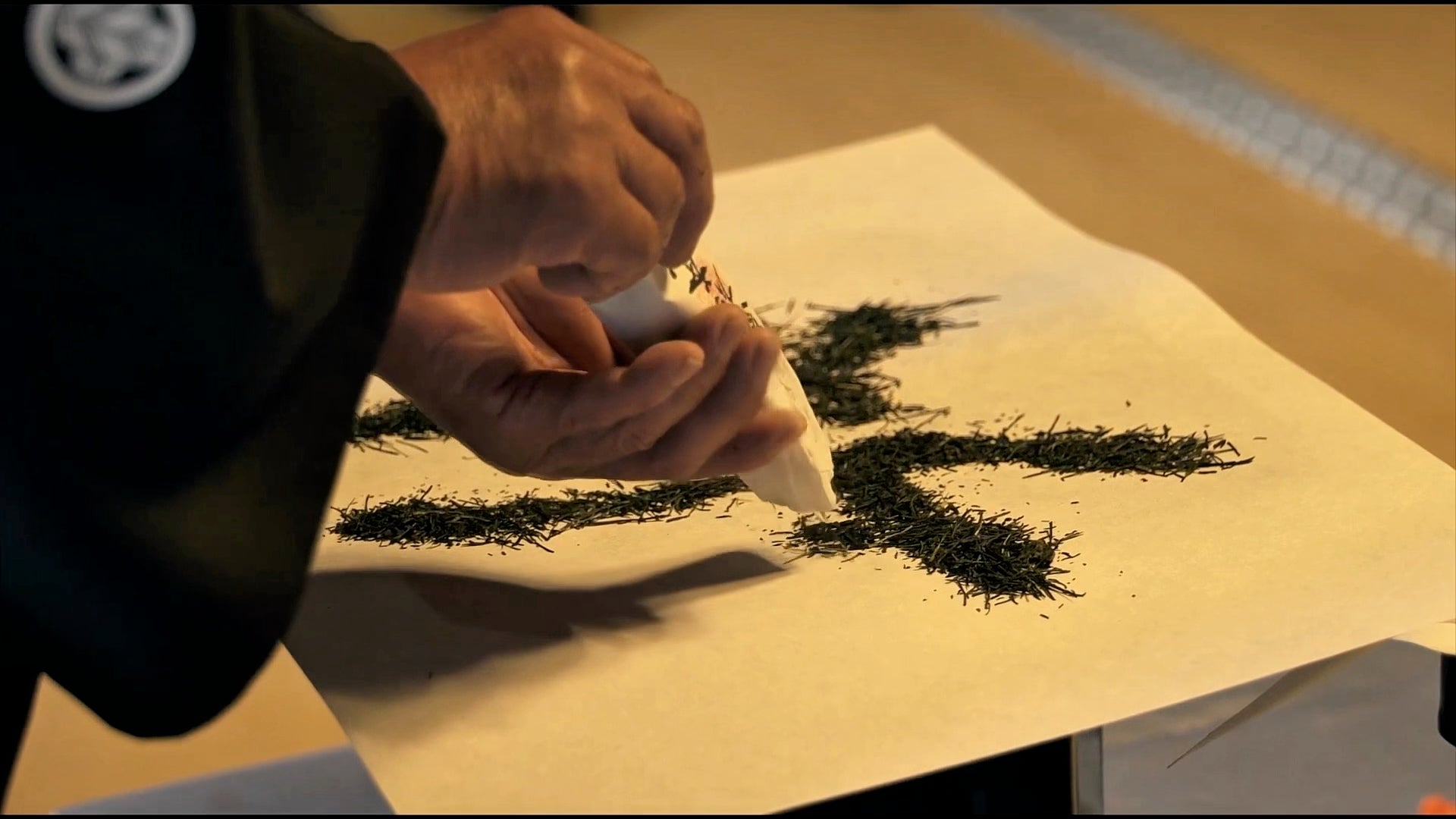

Temomicha (手揉み茶) Temomicha means “hand-rolled tea.” It is a rare and labor-intensive method of tea processing where each leaf is carefully rolled by hand—a craft passed down for generations. The result is a tea with exceptional aroma, clarity, and leaf integrity, often reserved for competitions or special tastings. It’s a living testament to the artistry behind Japanese tea.

Umami (旨み) Umami is one of the five basic tastes, alongside sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. In Japanese tea, it refers to the savory, broth-like flavor that comes from L-theanine and amino acids, especially in shade-grown teas like Gyokuro and Matcha. Umami gives tea its depth, roundness, and satisfying finish, distinguishing premium Japanese green tea from other types worldwide.

Usucha (薄茶) Usucha, or “thin tea,” is the most common way Matcha is prepared in modern tea ceremonies. Using about 2 grams of Matcha whisked with hot water, it creates a light, frothy, and approachable cup. Usucha is typically served individually, in contrast to Koicha, which is shared. It embodies both accessibility and grace within tea culture.

Wabi-Sabi (侘寂) Wabi-Sabi is a deeply rooted Japanese aesthetic philosophy that embraces the beauty of imperfection, impermanence, and simplicity. In tea culture, it is reflected in the subdued elegance of rustic ceramics, the quiet charm of a weathered teahouse, or the fleeting moment of steam rising from a freshly whisked bowl of Matcha. Wabi-Sabi teaches us to find peace in the natural cycle of growth and decay, and to cherish things that are imperfect, modest, and transient—a core sensibility of the Japanese tea ceremony.

Wakei-Seijaku (和敬静寂) Wakei-Seijaku is the foundational principle of Chadō (The Way of Tea), composed of four kanji that translate to: Wa (和): Harmony / Kei (敬): Respect /Sei (清): Purity /Jaku (寂): Tranquility.

These four ideals guide every aspect of the tea ceremony—from the relationship between host and guest, to the arrangement of the room, to the gestures performed during preparation. Practicing Wakei-Seijaku means cultivating an environment where silence, intention, and connection can flourish.

Wa-kōcha (和紅茶) Wa-kōcha means “Japanese black tea,” with wa (和) signifying Japanese origin and kōcha (紅茶) meaning black tea. Unlike imported black teas from India or Sri Lanka, Wa-kōcha is typically milder, smoother, and naturally sweet, often with floral or honey-like notes. It is produced using Japanese cultivars, giving it a distinct character that reflects local terroir and craftsmanship. Wa-kōcha represents Japan’s contribution to the world of black tea, offering a more delicate and refined alternative.

Japanese tea is more than a beverage—it is a living tradition shaped by centuries of craftsmanship, philosophy, and quiet beauty. From the tools of the tea ceremony to the subtle distinctions between tea types and preparation methods, each word carries with it a piece of culture, history, and meaning. By learning the language of tea, we gain a deeper appreciation for not only how it is made, but how it is shared—with intention, grace, and respect.

If this glossary has inspired you to dive deeper into the world of Japanese tea, we invite you to explore our curated collection of artisanal teas, read more on our blog, or join us on social media for weekly stories from the fields of Shizuoka and beyond. Whether you’re a lifelong tea enthusiast or just beginning your journey, there is always more to discover—one sip, one word, one moment at a time.

👉Browse our teas | 🍵Follow us on Instagram | 📖Read more tea stories